Fine-Tuning LLMs with Non-Differentiable Human Feedback + RL

The blog is focused on giving you an intuition of why even using non-differentiable reward function we are able to use Group Relative Position Optimization (GRPO) for fine-tuning LLMs.

Why Do We Need Differentiable Loss Functions?

Deep learning models—like the ones powering LLMs or your favorite image generator—are trained using gradient-based optimization algorithms, stuff like gradient descent. These algorithms are basically the GPS for training: they figure out how to adjust the model’s parameters (those millions of tiny weights) to make the loss—the “how wrong are we?” score—as small as possible. To do that, they need to calculate the gradient of the loss function with respect to those parameters. Think of the gradient as a little arrow saying, “Nudge this weight up a bit, and the loss goes down,” or “Tweak that one down, it’s messing things up.”

Now, here’s the catch: gradients only exist if the loss function is differentiable. That just means it’s smooth enough that we can measure how it changes when we tweak the inputs—no sudden jumps or breaks where the slope goes haywire.

What Happens If the Loss Function Isn’t Differentiable?

If the loss function isn’t differentiable, gradient-based optimization—the backbone of deep learning—falls apart. Those little arrows we rely on? Gone. Without them, we can’t tell the model which way to tweak its weights, and it’s stuck, unable to learn. Sure, there are derivative-free optimization methods out there—like random search or evolutionary algorithms. Those methods are way less efficient, especially when you’re dealing with the crazy high-dimensional parameter spaces in deep learning models.

Here’s something that might trip you up: in Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO), reward functions don’t have to be differentiable—think stuff like the length of a generated response or whether it even contains an answer. So how are we still using GRPO to fine-tune LLMs, which live and breathe gradients?

TLDR:

“The advantage (normalized reward) acts as a constant or scaling factor in the GRPO Loss”

GRPO, cooked up by the DeepSeek team, is a twist on reinforcement learning (RL) that’s all about efficiency and stability when fine-tuning LLMs. It builds on the idea of PPO—using human feedback to guide the model—but it’s got some unique tricks up its sleeve, especially with how it handles rewards. Let’s break it down.

The Basics of GRPO

In GRPO, the LLM is your policy ($\pi_\theta$), spitting out responses based on prompts. You’ve got a reward model ($R_\phi$)—trained on human feedback or reward function—that scores those responses.

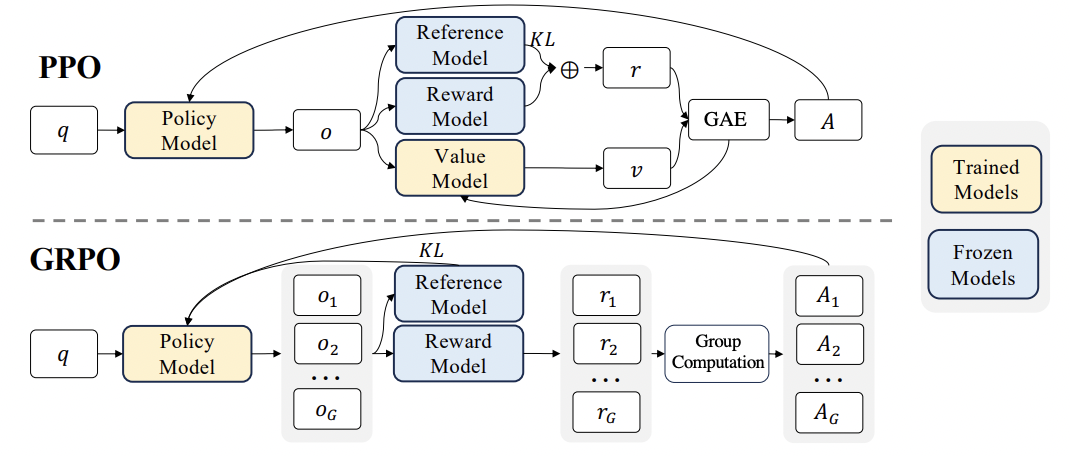

Unlike traditional RL methods like PPO, GRPO skips the critic (a separate model estimating future rewards), which cuts compute costs by about 50%. Instead, it uses a clever way to judge how good a response is by comparing it to a group of other responses for the same prompt. That’s where the “group relative” part comes in.

The Reward Function in GRPO

Here’s where it gets interesting: the reward function in GRPO doesn’t need to be differentiable. It could be something simple and rule-based, like:

- “How long is this response?” (e.g., word count)

- “Does it actually answer the question?” (e.g., 1 if yes, 0 if no)

- “Is it toxic?” (e.g., a binary flag from a rule-based checker)

These are discrete, step-like signals—not smooth curves you’d expect gradients to flow from. But GRPO still can use a reward model $R_\phi$ to assign scores, and that’s often a neural network trained on human feedback (like “this response is better than that one”). So, you might have a mix: a differentiable reward model for some parts, plus these non-differentiable, rule-based rewards tossed in.

The GRPO Loss Function

Demonstration of PPO and GRPO. GRPO foregoes the value model, instead estimating the baseline from group scores, significantly reducing training resources. (Source: DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models)

Let’s get to the meat of it—the loss function that makes GRPO tick. The goal is to tweak the LLM’s parameters ($\theta$) to maximize rewards, but with some guardrails to keep things stable. Here’s the equation:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{GRPO}}(\theta) = \mathcal{L}_{\text{clip}}(\theta) - w_1 \mathbb{D}_{\text{KL}}(\pi_\theta || \pi_{\text{orig}})\]$\mathcal{L}_{\text{clip}}(\theta)$: This is the clipped surrogate loss, adapted from PPO for GRPO. It encourages better responses while preventing excessive policy changes:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{clip}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) A_t, \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon) A_t \right) \right]\]Where:

-

$r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t s_t)}{\pi_{\text{old}}(a_t s_t)}$ is the probability ratio—comparing how likely the new policy is to generate this response versus the old policy - $A_t$ is the advantage, measuring how much better (or worse) this response is compared to others in the group

- The clip function keeps changes bounded (typically $\epsilon = 0.2$) to maintain stability

| $\mathbb{D}{\text{KL}}(\pi\theta | \pi_{\text{orig}})$: This KL divergence term acts as a constraint, keeping the updated policy from straying too far from the original. The weight $w_1$ (usually around 0.1) controls this constraint’s strength. |

A key innovation in GRPO is how it calculates the advantage ($A_t$). Instead of using a separate critic model like PPO does, GRPO computes it by comparing a response’s reward to the group statistics:

\[A_i = \frac{R_\phi(r_i) - \text{mean}(\mathcal{G})}{\text{std}(\mathcal{G})}\]Where $R_\phi(r_i)$ is the reward for response $r_i$, and $\mathcal{G}$ represents the group of responses for the same prompt.

The $\text{mean}(\mathcal{G})$ and $\text{std}(\mathcal{G})$ terms represent the average and standard deviation of rewards across the group, respectively. This normalization transforms raw rewards into relative advantages, making training more stable by comparing each response to its peers.

Why Non-Differentiable Rewards Still Work in GRPO

Okay, so how does GRPO handle rewards like “length of the generation” or “contains an answer,” which aren’t differentiable? Here’s the trick: the reward itself doesn’t need to be differentiable—what matters is how it’s used in the optimization. Let’s unpack this:

- Rewards Are Just Scores:

- In GRPO, the reward function—whether it’s a fancy neural network $R_\phi$ or a simple rule like “1 if it answers, 0 if not”—is only there to assign a number to each response. That number (the reward) isn’t differentiated directly. It’s a fixed value that feeds into the advantage calculation.

- Advantages Drive the Gradients:

- The advantage $A_t$ is computed from those rewards, and it’s just a normalized comparison (better or worse than the group). It’s not differentiated either—it’s a constant for each response.

- The differentiable part comes in the policy update. The loss $\mathcal{L}{\text{clip}}$ depends on the LLM’s probabilities ($\pi\theta$), which are differentiable. The gradients flow through the policy, not the reward or advantage directly.

Now, here’s the part that clicked for me: in the GRPO loss function, the advantage $A_t$ acts like a constant or scaling factor. Check this out:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{clip}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) A_t, clip(r_t(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon) A_t \right) \right]\]The $r_t(\theta)$ part—the probability ratio—is what the LLM tweaks, and it’s totally differentiable. The advantage $A_t$? It’s just a number we calculate from the rewards, like “this response is 1.5 better than average.” It scales how much we push the model toward or away from that response, but we don’t need to differentiate it. It’s fixed for that step.

So, even if the reward function is something chunky and non-differentiable—like “1 if the answer’s there, 0 if not”—it doesn’t matter. The reward spits out a score, we turn it into an advantage, and that advantage just rides along as a multiplier. The gradients flow through the LLM’s policy, not the reward itself. It’s like giving the model a scorecard and saying, “Here’s how you did—now adjust!” The scorecard doesn’t need a slope; it just needs to exist.

For additional perspectives on GRPO, check out these papers and blog posts: